Charity Brings Cutting-Edge Education to China’s Most Deprived

In the country’s hinterland, the Adream Foundation is helping rural schoolchildren study their way out of poverty.

This article is the first in a two-part series on an education charity in China.

In late June, I sat with Wang Fuqiang, a 13-year-old Tibetan boy, on the roof of his family’s cottage in Songgang, an ethnic minority village in Barkam City, located in southwestern China’s Sichuan province. From Monday to Friday during the school year, Wang lived at a boarding house for primary school students, a 10-minute walk away from home across a potato field blooming with blue flowers.

In a tattered T-shirt and a jacket missing a zipper, Fuqiang sat in the sunshine alongside a visitor, a Han girl called Yang Yiyan. The youngest daughter of a Beijing-based property developer, Yiyan is four years younger than Fuqiang, but a little taller. She and her parents had come to Barkam with Adream Foundation, one of China’s most highly regarded education charities, as part of a summer camp for generous donors and their families.

Their respective fathers, Yang Zhongguo and Wang Songbai, chatted downstairs. Unable to bear the crushing poverty of family life any longer, Songbai’s wife divorced him when Fuqiang was little. The government found Songbai work as a security guard in the nearby county-level town, a job that took him away from Fuqiang for long periods at a time. Fuqiang was left in the care of the village primary school: Free boarding is available for all students from grades one through nine in Barkam, along with a monthly 170-yuan ($25) state grant, as long as they stay at school from Monday to Friday.

Fuqiang, who is in the sixth grade, will graduate from Songgang next year. A lover of basketball, his dream is to one day become a coach; at just under 5 feet tall, he says he can’t become a professional player. Too poor to afford new sneakers, he tears across the court in a pair of well-worn old ones. “When I’m happy, I come up here and sleep on the rooftop,” Fuqiang says. “When I’m feeling down, I go and play basketball.”

After a while, the two teenagers come down from the roof and head out toward a patch of ground in the village so that Fuqiang can show Yiyan his backflip. Downstairs, Yiyan’s father tries to cheer Songbai up, encouraging him to find a new wife and make the family whole again. Later that evening, after dinner with the city’s local officials, the Yangs come back to the cottage with gifts: a basketball, a pair of sneakers, and a tracksuit for Fuqiang.

Ten years ago, Adream’s founder, Pan Jiangxue, came to Barkam and set up a well-stocked reading room in the local middle school. Dubbed the “Dream Center” and outfitted with computers and internet access, it became an oasis to a generation of students who otherwise had little opportunity to read anything other than their textbooks. Fuqiang attends one class a week at another Dream Center in Songgang Primary School. Aside from sports, he loves reading and writing.

A decade later, nearly 2,600 Dream Centers has been built across the country. They are used by around 3 million students, mostly in inland China. In addition to donating books and refitting classrooms, Adream has brought new courses and teaching methods to Barkam. The foundation has developed more than 40 “Dream Classes” showing kids how to plan trips, exercise thrift, perform first aid, and even make a fashion show out of scrap newspaper. Backed by local government support, the foundation has trained more than 60,000 teachers at its partner schools.

For many years, Chinese charities have focused on education as a means to bring social equality to future generations. Back in 1989, the China Youth League launched Project Hope through its affiliate, the China Youth Development Foundation, which aimed to lower student dropout rates and improve school facilities. Within two decades, Project Hope raised enough funding to rebuild 13,000 schools and support nearly 3 million students who would otherwise have dropped out of school due to poverty.

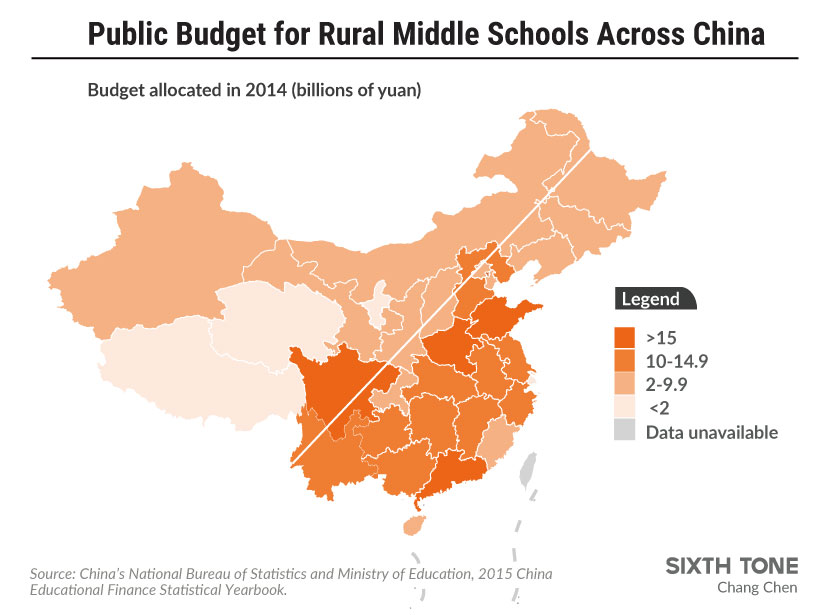

However, Project Hope’s work began to decline when the Chinese government guaranteed nine years of free education for all rural students in 2006. At the same time, the rural student population began to shrink, as more and more families migrated to the cities in search of work. Now, many of Project Hope’s countryside schools lie deserted.

Drawing on the lessons of Project Hope, Pan has ensured that Adream has evolved alongside the changing face of education in China. Twenty years ago, the country’s education charities aimed to get every child into a classroom. When Pan started Adream a decade later, it was to build better schools with high-quality facilities. Today, the goal is to inspire a sense of confidence, composure, and dignity among future generations.

Local students dress up in Tibetan costume during a celebration marking 10 years since the founding of the Dream Center at Barkam No. 2 Middle School in Barkam County, Sichuan province, June 26, 2017. Courtesy of Adream Foundation

The first Dream Center in Barkam, built just 10 years ago, is now a museum. Next to it, a sixth-generation Dream Center is preparing for the fall semester, equipped with tablet computers, virtual reality classes, and 3-D printers. Barkam’s local Party secretary, Zhang Peiyun, is also of Tibetan heritage. Along with local education officials, schoolteachers, and the students themselves, he took part in a ceremony to mark the opening of the Dream Center’s latest incarnation.

During the ceremony, four sixth-graders — whose parents are long-time Adream donors — from an international school in Shanghai performed as a string quartet. Sitting on the floor in front of them, the local students, none of whom had been taught music, looked on. Later, a Shanghai-based music teacher gave each local student a colored bell, instructing them to hit it when he called out a certain color. Forty minutes later, the well-drilled local students were providing a splendid accompaniment to the quartet’s version of the famed Chinese song, “Jasmine Flower.”

Donor families take pride in their good deeds and often encourage their children to be philanthropic, too. It is equally important for children from different parts of society to interact with and learn from one another. Most kids from donor families are either studying abroad or preparing to do so. They sit on the opposite side of the wealth gap from their counterparts in Barkam, many of whom can only dream of the luxury of living in a rich, modern metropolis like Shanghai.

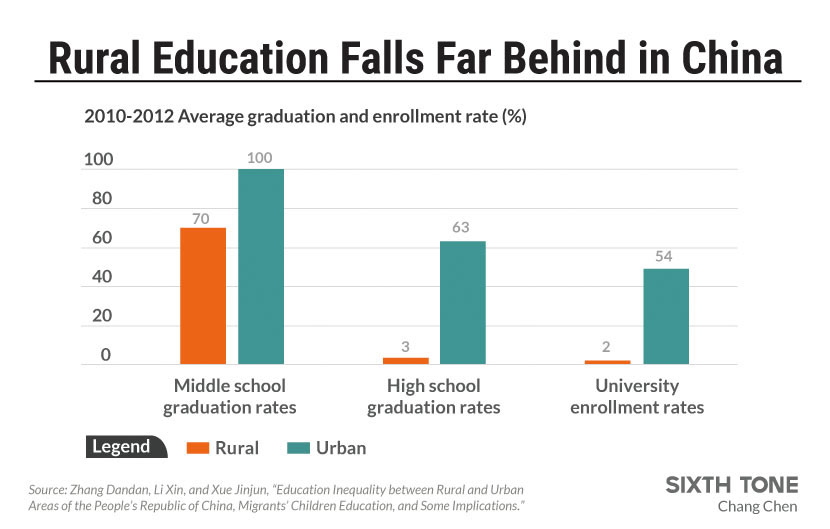

In China, the word “underprivileged” used to have a tangible relationship to material poverty: no food, no clothes, and no school. In some places, that definition still stands, but in others, underprivileged children are often exposed to evidence of a vast, but isolated, world of wealth — one which they are locked out of from birth. This is why charitable projects like Dream Centers are so important, for empowering every child to think bigger and casting off the strictures of poverty is key to giving every Chinese student a fair education.

Editor: Matthew Walsh.